To each his own rhythm: children who grow up out of step

Read this article published in Sciences Humaines (Monthly No. 329 – October 2020)

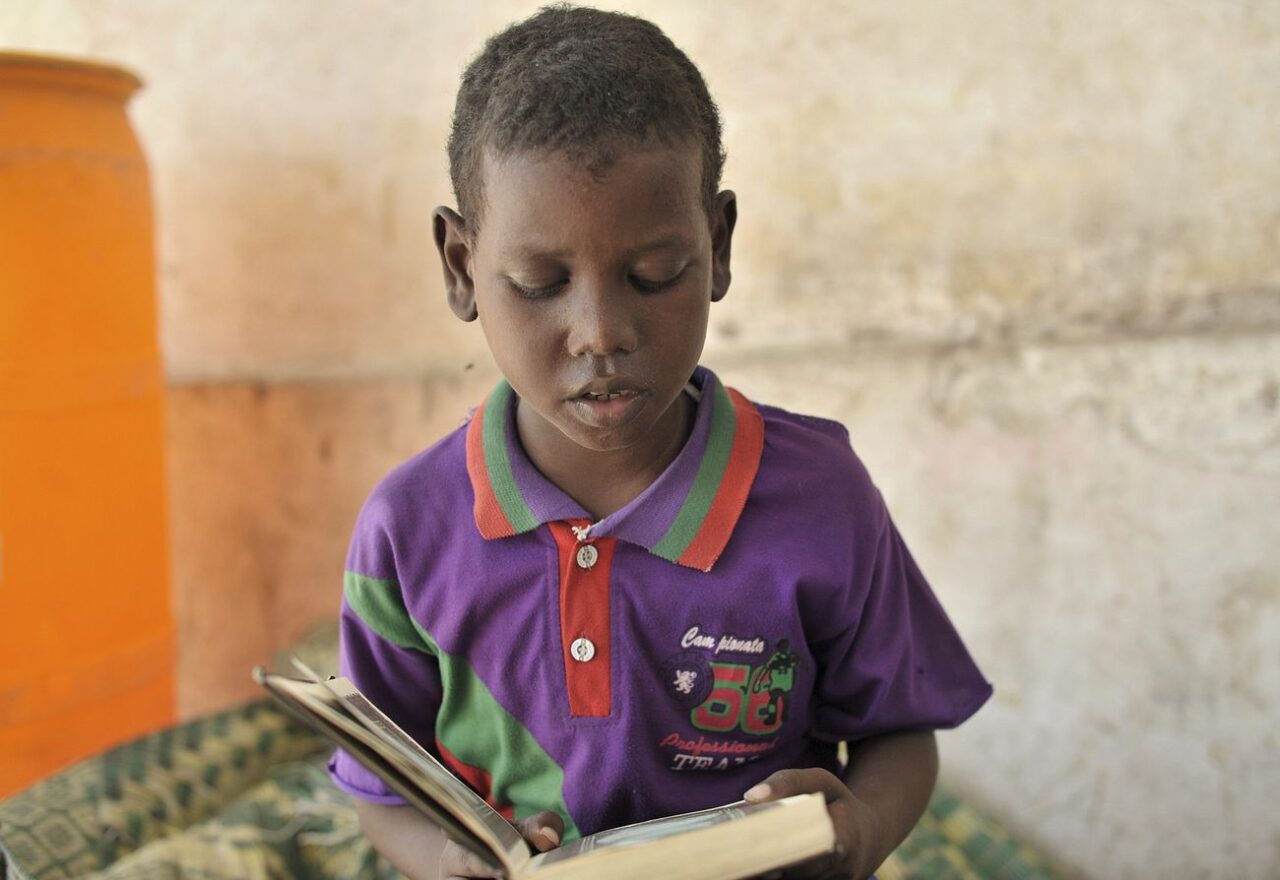

A child’s development is punctuated by norms: he or she must be able to speak at such and such an age, read and count at another… Children who step out of line risk finding themselves on the bangs of the school system. What if the problem wasn’t the atypical development of these children, but rather the normativity of our expectations?

From an early age, Bastien’s teachers predicted a life punctuated by failure and academic difficulties. Don’t get your hopes up, » they told his parents. If he reaches CM2, it’s already good. If he makes it past middle school, it would be a miracle! Bastien suffers from dyslexia and ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) with hyperactivity. Some ten years of struggle, sacrifice and care later, Bastien entered a top business school. Today, this student-who-was-not-supposed-to-pass-the-CM2, has founded a communications company and manages a team of twenty people. And when you ask him what enabled him to escape the « no hope » box he was condemned to as a child, Bastien replies: « my parents ». They moved to be closer to the best specialists, took time off work to train in the care of atypical children, and took out loans to finance their care. Like their teachers, they have always had high hopes for their son. Bastien’s victory is, in the end, the victory of his whole family.

The delicate boundary between normal and pathological

Children who, like Bastien, deviate from the norm and grow up « out of step » are not rare. 1 to 10% of children suffer from a « dys » disorder[1], 18% are affected by a developmental problem. And if we include emotional and behavioral problems, this prevalence rises to 22%[2]! These developmental trajectories, considered « out of the ordinary », are multifactorial: they are based not only on the child’s cerebral maturation, but also on the social, adaptive, cultural and family components of his or her environment[3]. Given the multiplicity of these children’s profiles, one question remains unanswered: is the boundary between normal and pathological as objective and infallible as we might think? Of course not. This very boundary, which has always been the subject of debate among scientists, remains dependent on a society, an era, a set of determined expectations with regard to children’s development and behavior.

In another era, Bastien’s ADHD might not have been a handicap.

Let’s take the example of Bastien’s ADHD. As a 2009 INSERM report[4] reminds us, its prevalence varies from 0.4% to 16.6%[5] depending on the country, the diagnostic method used, the measurement criteria used and the definition of the population concerned. Bastien might therefore have been diagnosed with ADHD in one study and not in another. The identification of this disorder also remains dependent on a given era. In the ancient population of hunter-gatherers and nomads, for example, ADHD profiles like Bastien’s would have been highly adapted. Hyper-alert by nature, they would have been better hunters than their congeners, optimizing their chances of survival and those of their community. The evolution towards a more sedentary, industrial lifestyle is, in the end, less suited to them. Furthermore, according to research published in 2011 in the journal Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, children diagnosed with ADHD show improved concentration and better control of their impulsivity when playing outdoors[6]. In other words, when they approach the living conditions for which mammals are programmed (living on the move and in the open air), their symptomatology is greatly reduced. This raises another question: don’t children’s problems only emerge when we try to conform them to a lifestyle that’s not adapted to their specific characteristics? It’s worth remembering that one of the diagnostic criteria for many disorders is the significant and lasting interference of symptoms with the quality of the child’s school, social and family life. This, in turn, raises the question of school life (where symptomatology is generally most troublesome): is it these children who are not adapted to school life because of their identified disorder, or is it the expectations of school life that are not always adapted to the plurality of children’s profiles? The specificity of school (being sedentary for several hours a day in a confined space) and the uniformity of school expectations seem to be explanatory factors for certain childhood disorders. Which reminds us of Albert Einstein’s legendary quote: « If you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its life believing it is stupid ».

The importance of positive parenting

As Bastien’s testimonial confirms, a parent’s view of their child’s particularities also plays a major role in their child’s development and success: « we have confidence in you », « you’ll make it », « you’re capable ». A 2006 study showed that parental optimism increases the child’s chances of success, which in turn increases the child’s disposition to optimism[7]. Various studies carried out in schools have shown a link between optimistic thinking in children and better performance at school and university[8]. This finding intersects with the « Pygmalion effect », a concept that has been the subject of heated debate for some thirty years. According to this form of self-fulfilling prophecy, belief in an individual’s success on the part of an authority (a teacher or a parent) leads to a real improvement in that individual’s performance[9]. In other words, the mere fact of believing in a child’s success would increase his or her probability of success. So, despite a child’s atypical developmental trajectory and the pessimism of teachers, parental attitude can, under certain conditions, be a differentiating factor in the prognosis of his or her evolution. And, consequently, their professional success and fulfillment in adulthood. What happens to these extraordinary children in adulthood?

What happens to these « non-standard » children when they grow up?

For some children, the disorders that affected their schooling can continue to be a source of serious difficulties in their professional and personal lives into adulthood. For others, the wheel turns as soon as they leave the normative confines of school. They end up finding the fulfillment they’ve always lacked, building a tailor-made existence in line with their characteristics. Sometimes, the particularities that handicapped them during their schooling even become an asset in the professional world. Profiles with ADHD are known for their independence, speed of execution and dynamism. They can excel in extraordinary and/or far-from-routine positions such as expert, consultant, trainer, speaker, actor. Recent 2018 research published in The Journal of Creative Behavior[10], highlights in adults with ADHD their tendency to resist conformity. This distancing from conventional information in favor of new data predisposes them to a talent for innovation. Dyslexic adults, on the other hand, are known for their creativity, tenacity and capacity for work. [11]. The learning difficulties they have faced have enabled them to develop compensatory skills, perseverance and creativity to work around problems. Research has shown that dyslexic business leaders are very numerous. While dyslexia affects 4% of the population, the prevalence climbs to 20% among managers. The same applies to Asperger’s adults. Some companies seek out these profiles, known for their exceptional memory, stability and compulsive tendency to gather as much information as possible on a very specific area of expertise. Nobel Prize-winning author Thomas Mann, Gandhi, Winston Churchill, German film-maker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Paul Cézanne… Many of these out-of-the-box personalities had a schooling punctuated by failures that ended up making their mark on the history of their country… Or just by blossoming into adulthood. After all, as Idriss Aberkane, doctor in cognitive neuroscience and French essayist concludes in his book « Libérez votre cerveau » (Robert Laffont, 2016): « We are not here to conform to an imprint, but to leave our own ».

__________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

Neurodiversity: difference is not a deficiency

This question of inter-individual difference is at the heart of a debate closely linked to Autism Spectrum Disorders, that of neurodiversity. According to this concept, which appeared publicly in 1998 in the article Neurodiversity by writer Harvey Blume [14]Individuals whose functioning differs from that of the majority, and who deviate from the norms (set according to that same majority), are not deficient but « neuro-atypical ». Like biodiversity, neurodiversity refers to neurological variability in human beings, including different neurological functions. Individuals with ASD are neither deficient nor defective. They simply function differently from « neuro-typicals », a thesis widely defended by many associations and scientists, including Michelle Dawson, activist and researcher at the Université de Montréal. [15]. « … While I’m at it, you should know that I find it particularly interesting that my inability to learn your language is seen as a deficit while your inability to learn my language seems perfectly natural to you, given that people like me are described as mysterious and baffling. This, instead of admitting that it’s other people who are baffled… » testifies American Amanda Baggs, diagnosed with severe non-verbal autism, in her stunning video posted on You Tube. [16].

[1] A statistic that varies considerably depending on the study, the country, the period and the severity of the disorders studied.

[2] Glascoe, F. P. (2005). Screening for developmental and behavioral problems. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev, 11(3), 173-179.

[3] Resch, F. (2008). Developmental Psychapathology in Early Childhood: Interdisciplinary Challenges. In S. Papousek, Wurmser (Eds.), Disorders of Behavioral and Emotional Regulation in the First Years of Life: early risks and intervention in the developing parent-infant relationship (pp. 13-25). Washington: Zero to Three.

[4] Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale, Expertise opérationnelle. Santé de l’enfant : propositions pour un meilleur suivi. Paris: INSERM; 2009.

[5] Bursztejn C. Motor hyperactivity with attention deficit. Enfances Psy 2001;3(15):137-45

[6] Faber Taylor, A. et al (2011). Could Exposure to Everyday Green Spaces Help Treat ADHD? Evidence from Children’s Play Settings. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 3(3), 281-303.

[7] Heinonen K., Räikkönen K., Matthews K. A., Scheier M. F., Raitakari O. T., Pulkki L. & Keltikangas-Järvinen L. (2006) Socioeconomic status in childhood and adulthood: Associations with dispositional optimism and pessimism over a 21-year follow-up. Journal of Personality 74(4):1111-26. [aNB]

[8] Peterson, C., & Barrett, L. C. (1987). Explanatory style and academic performance among university freshman. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 603-607. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.603

[9] Davidson, O. B., & Eden, D. (2000). Remedial self-fulfilling prophecy: Two field experiments to prevent Golem effects among disadvantaged women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 386-398. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.386

[10] Holly A. White. Thinking « Outside the Box »: Unconstrained Creative Generation in Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 2018; DOI: 10.1002/jocb.382

[11] LauraMalié (2016). When dyslexia becomes a strength: testimonies from dyslexic adults on the assets of their learning disability within the professional world. Human medicine and pathology.

[12] Daniel Goleman, L’intelligence émotionnelle: comment transformer ses émotions en intelligenceTrad. T. Piélat, Paris, Éditions Robert Laffont, 1997.

[13] Parker, J. D., Creque Sr, R. E., Barnhart, D. L., Harris, J. I., Majeski, S. A., Wood, L. M., … Hogan, M. J. (2004). Academic achievement in high school: does emotional intelligence matter? Personality and Individual Differences, 37(7), 1321-1330.

Simon Guiller. Emotional competence and well-being in schools. Education. 2018. dumas01807923

[14] Harvey Blume (1998) « Neurodiversity: On the neurological underpinnings of geekdom », The Atlantic.

[15] https://distinctions.umontreal.ca/luniversite-honore/doctorats-honoris-causa/doctorats-honoris-causa-2013/profil/udemportraits/f/michelle-dawson-1/

[16] Video translated into French: https: //www.youtube.com/watch?v=1EvvotxGq4k